Appendix

RCAF History

Winston Churchill once described the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan

(BCATP) as "one of the major factors, and possibly the decisive factor in the

war". It is difficult to gauge the impact of the BCATP on the events of World War II,

however, and the eventual Allied victory. Almost half of all Commonwealth air crew spent part of their training in the BCATP; the Plan graduated a total of 131,553 aircrew over the course of the war. One third of the sorties conducted by the Royal Air Force’s Bomber

Command, which helped loosen Hitler’s grip on Europe, were conducted by those

trained through the BCATP. Other graduates protected the lifeline over the

Atlantic, which sustained Britain throughout the war. The Plan undoubtedly contributed in countless ways to the war effort. Many died for it; over 17,000 aircrew from the Royal

Canadian Air Force (RCAF) alone were killed, and almost 900 recruits died during training.

While many of the training sites were quickly abandoned and forgotten, or put

to other, non-military uses, the BCATP nevertheless had lasting influence in

Canada.

The Plan served to strengthen Canada’s status as a sovereign nation. It was a

responsibility of an unprecedented level, requiring a great organizational and

logistical capacity, and costing over $2.2 billion, with Canada’s share accounting for 72 percent of the cost. It allowed for the development of a stronger, permanent, national Royal Canadian Air Force.

Training schools were spread out across the country, and divided into four

training commands. No. 1 Training Command encompassed most of Ontario (except for one school in Western Ontario, which fell into No. 2), with a headquarters in Toronto.

No. 2 encompassed Manitoba and approximately half of the schools in

Saskatchewan, and was headquartered in Winnipeg. Schools in Quebec and the three Maritime Provinces fell into No. 3 Training Command, headquartered in Montreal. Finally, No. 4

encompassed the rest of the schools in Saskatchewan along with those in Alberta

and British Columbia. No. 4 Training Command headquarters was originally located in Regina, but was relocated to Calgary.

Most of the air-bases were built in the prairies, as they had abundant flat,

open space, good weather and a low population density. A total of 120 bases were needed, and two thirds of them had to be built from scratch. Newly-hired carpenters and labourers built more than 700 hangars. They also built messes, canteens, offices, drill halls, classrooms, dining rooms and barracks, over 7,000 buildings in total. The cost of these buildings reached $80,000,000.

The economic benefits continued throughout the war, helping to pull Canadian communities out of the Great Depression of the 1930s. With each new station came personnel, and with the influx of new people, business in local establishments duly improved. Industry improved, especially aircraft and munitions manufacturing as

well as mining, which provided the necessary raw materials of copper, nickel and iron.

The first pilot course graduated their class on September 30, 1939, consisting

of 39 students. The numbers rose to 3,113 a month in late 1942, peaking at 5,157 graduates in October 1943. By June 1944 there was a surplus of pilots, and the plan started winding down. Recruiting stopped, and by October, schools started to close down. The last classes graduated on March 29,1945; two days later, the Plan expired.

Background

In World War I, Canadian Air Force personnel were integrated into units of the Royal Air Force (RAF). One part of the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan

(BCATP) agreement signed in 1939 allowed for the existence of Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) units overseas. The terms of the agreement were vague, and allowed for broad interpretation on the part of both the British and the Canadian governments. The Canadians understood it to mean that, eventually, all Canadian graduates of the BCATP would serve in RCAF units overseas. The British took it to mean that a limited number of RCAF squadrons would be formed, with the remainder of graduates serving in RAF units. The tension between these two positions would persist throughout the war.

The Royal Canadian Air Force was founded in 1924 and the fledgling outfit had only 324 officers and airmen, rickety relics to fly and duties that were a far cry from the military such as putting out fires to delivering treaty money to the Indians, 61 years ago. Actually the first military flight took place some 15 years before this when John McCurdy tried to convince the Army brass at Pettawawa, Ontario, that planes could be useful instruments of war. He is the one who made the first powered flight in Canada when his Silver Dart rose from the ice of Nova Scotia's Baddeck Bay. The Army showed no interest but five years later World War 1 began and the Canadian Aviation Corps was formed -three persons and one $5000 plane. However it ceased to exist a year later so Canadians rushed to join Britain's Royal Flying Corps which became the Royal Air Force in 1918. Also, the British had opened up their own training facilities in Canada and by war's end had produced pilots in Canada. Interesting also was that at the end of the war, a study showed that more than 13000 Canadians were then serving in the RAF so the Federal Governement decided to have its own organization.

In England, the Canadian Air Force was born with Billy Bishop as the first

Commander but it disbanded a year later to begin again as the Royal Canadian Air

Force in 1924. Development took place slowly but surely.

In the later thirties, the RCAF started to gear up after the depression and the

budget soared. Indeed by the end of World War II, almost 250 000 had enlisted and 93000 had served overseas. The RCAF was easily the most dangerous of the three services.

Though RCAF accounted for only 23% of enlistments, 41% of the country's war dead were airmen and airwomen.

Most of the 17000 and some say 18000 who died were killed on bombing raids over Germany but there were many who died as a result of training accidents.

The RCAF after the war emerged as the fourth largest Air Force with 48

Squadrons flying in Europe and the Far East and 37 at home. It had also provided overseeing the development of the British Air Commonwealth Training Plan which produced 131 000 pilots and aircrew in five years and 73 000 were Canadian -a very impressive record of which we should be proud.

Navigating by the stars perhaps

If their targets were beyond Gee's limited range, observers had to rely on

technology first developed in the early 18th century — star sightings using the

sextant.

But the sextant was useless in cloudy weather, and even if a star sighting could

be made, by the time the necessary calculations were completed, the aircraft would

be miles further into its flight. So observers often had to depend on dead

reckoning and the sighting of landmarks, not an easy thing to do over a continent that was often covered with cloud and industrial haze.

Dead reckoning was little more than an educated guess about an aircraft's

whereabouts at any particular time, based on airspeed, estimated drift caused by

contrary winds, and passage of time determined by chronometer. Landmarks were

dead last in the navigator's list of useful tools: The reflection of moonlight on

ocean waves could be mistaken for twinkling lights, and only the brightest moonlight could reveal details on the ground.

Bomber Command had to walk a tightrope when it came to planning the dates

for missions. Only a few nights each year were truly ideal for missions to

distant German targets: they were the longer nights of late autumn, winter, and early

spring, when the cloak of night might hide bombers from night fighters. But not any dark night would do: there had to be moonlight bright enough for navigators/bomb aimers to see the ground and their targets.

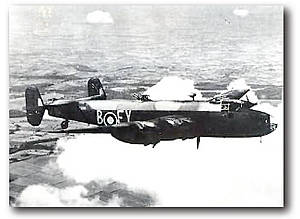

Halifax

- A Halifax MV Rolls Royce Merlin Engines Wing Span is 99 feet.This is almost

Although it was overshadowed by the Avro Lancaster, the Halifax played a vital role in Bomber Command operations. The Halifax unlike the Lancaster was called upon to serve in a variety of roles including glider towing, maritime patrol and casualty evacuation. The Halifax design stemmed from the same ministry request that produced the Avro Manchester. Both bombers were designed to replace the Wellington, Hampden and Whitley in the medium bomber role. When no twin engine layout was able to produce the needed power Handley-Page proposed the installation of four Rolls Royce Merlin engines, which resulted in taking the aircraft into the heavy bomber role.

Altogether 6176 Halifaxs were built for the RAF, in many versions. Later bombers had more powerful engines, including the 1615 -1800 Bristol Hercules radial on the Marks III, VI, and VII. The design was improved, with a streamlined nose instead of a turret, to improve her performance and so reduce losses. Some Halifax bombers operated against the Africa Korps, from Egypt; others flew as special duties squadron, dropping agents and arms by parachute to help the Resistance movement in Europe.

In other forms, Halifaxs served with distinction with Coastal Command and as

paratroop transports and glider tugs.

Names painted on the sides of RCAF Halifax bombers, like "Willy the Wolf", "The Champ", "Big Chief Wa-Hoo", and "Vicky the Vicious Virgin", reflected the affection that Canadian wartime crews felt for the big four engine bomber type. It could absorb tremendous punishment and still fly home. One Halifax aircraft, named "Friday The Thirteenth", survived 128 sorties. The Halifax was perhaps overshadowed by its larger cousin in Bomber Command, the Avro Lancaster, but many Canadian crews were more than satisfied with the aircraft type and the type was perhaps Canada's most important bomber in World War II.

Designation: Mk I,II,III,IV,V,VI,VII

Model No.: HP 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63 Role: Bomber, ASW, Transport & Glider Tug Quantity in Service: 84 Mk I, 1,977 Mk II, 2,091 Mk III 904 Mk V, 467 Mk VI, 35 Mk VII Service: RCAF / RAF

Taken on Strength: 1940

Struck off Strength: 1945

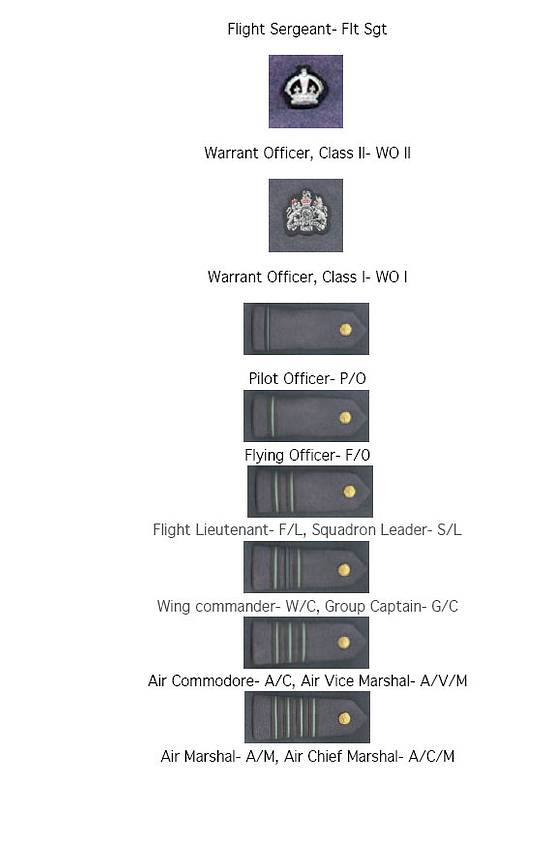

Ranks

During the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan (BCATP), upon entering into

the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF), one was normally given the rank of

Aircraftman 2nd Class (AC2) and a Standard (S) trade grouping. A member, or former member, of the Royal Canadian Air Cadets who had served three continuous years in a Cadet Squadron and attended two summer training camps, or one summer training camp and had completed the Senior Leader’s Course, the Drill Instructor’s Course, or the Flying Scholarship, was granted a classification of Aircraftman 1st Class (AC1) upon enrollment.

After one had completed six months of satisfactory service, airmen/airwomen

were reclassified as AC1. Then, after subsequent year of satisfactory service,

airmen were reclassified as Leading Aircraftman (LAC).

Individuals who were previously skilled in an RCAF trade were usually granted a

trade grouping that was commensurate with their experience upon enrollment.

aircrew

classifications and each was responsible for performing certain duties on

operations. This section will illustrate the classifications and what they entailed.

The aircrew classifications one could enlist for were:

Pilot

The majority of men who presented themselves for enlistment in the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) during World

War II had high hopes of becoming a pilot. While many men succeeded, more were trained in other trades. Most men felt that a pilot commission was glamourous compared to others, but the

pilots themselves would be the first to say that they relied upon other crew members on operations.

A pilot’s training was intensive. After Initial Training School (ITS), he attended Elementary Flying Training School (EFTS), Service Flying Training School (SFTS), was then posted to an Operational Training Unit or General Reconnaissance School and eventually, sent overseas, or kept in Canada to defend the homefront or train other pilots.

After EFTS, pilots who were going to be trained as fighter pilots were posted to

a SFTS where they would be trained, usually on Harvard aircraft, comparable to

what they would be using in combat. Men who were chosen to pilot bomber, coastal or transport operations were posted to a SFTS where they could train on larger,

dual engine aircraft such as Avro Anson, Cessna Cranes and Airspeed Oxfords.

In addition to their pilot flying training, as they were an aircraft commander

on operations, pilots were also trained in navigation, engines, airframe,

meteorology, wireless and photography. They were trained to be able to fly at any time of day, in any conditions. At SFTS, pilots specialized in advanced flying techniques such as night and instrument flying.

In the early years of the BCATP, the pilot training process took approximately

25 weeks. By 1944, the time pilots were required to spend in training had almost

doubled. In putting the Plan into practice, the Air Ministry soon learned how to make

improvements and took greater time to ensure that all aircrew were expertly

trained.

Navigator

Navigators could become straight navigators, or specialize to navigate bomber

or fighter aircraft. Nevertheless, a proficient navigator was essential to the

success of any aircraft on operation. Curtained away behind the pilot so as to conceal the lights he needed to calculate and log the aircraft’s course, navigators directed pilots to their destination and then back home again. If a navigator was not incredibly precise, the bomb aimer would miss his targets. These men needed to be trained intensively in navigational rules, calculations

and measurements to such a degree that they could pinpoint the position of the

aircraft while in flight without any external aid, also known as dead reckoning.

As the war progressed, so did navigational technology. Radios and astral observation were used to assist the navigator in his duties. However, since electronic devices could be interfered with and the stars are not always visible, dead reckoning was never replaced.

Air Bomber

Air Bombers were responsible for loading and dropping the bombs. They were required to be able to calculate the exact moment of when to drop the bomb load and then press the button to do so. He also had to learn to take photographs of the bombs after they had been dropped to record bomb destruction and enemy troop placement.

Air Observer In 1942, Canada’s Air Ministry revised bomber crews.

Instead of a crew being comprised of two pilots, an air observer and two wireless

operator/air gunners, it was decided that only one pilot was necessary for medium to heavy bombers and that the position of air observer, who up until this time was

responsible for both navigating and bomb dropping, would be broken up into two positions:

air bomber and navigator.

Thus a bomber crew from 1942 onward would usually consist

of one pilot, a navigator, an air bomber, a wireless operator/air gunner and one or

two straight air gunners. In a Lancaster bomber, a flight engineer was added to the crew.

Air Gunner (Gibb was a Mid-Upper Gunner)

In a Lancaster bomber as well as the Hamilton, a crew was comprised of seven members. There were two air gunners, one located in the mid-upper portion of the aircraft and another in the rear. As well as knowing how to target and shoot at the enemy aircraft, the air gunner was responsible for scanning the night sky

to spot enemy fighters and directing the pilot toward evasive action.

Wireless Operator

Wireless operators were trained to use the radio equipment on board an aircraft.

It was this person’s job to maintain communication with the world outside of the aircraft. In addition, a straight wireless operator was trained in using navigational equipment and was the member of the crew who would administer first aid if need be.

Flight Engineer

A flight engineer was the seventh and final member added to a heavy bomber crew. Essentially, the flight engineer was an aeroengine technician. Seated next to the pilot, he would assist in

take-offs, landings and monitor oil, fuel and pressure gauges. It was also this man's duty to take over the aircraft if anything happened to the pilot.

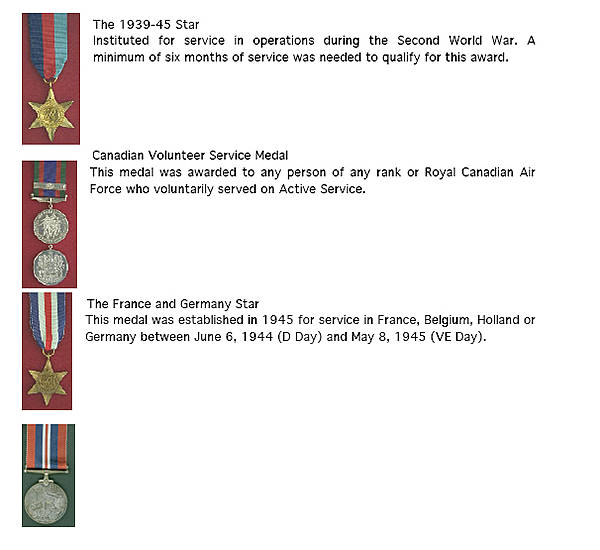

Medals

Uniform

RCAF Uniforms during World War II consisted of a jacket with four buttons, a belt cinched at the waist, a collared shirt and black tie, matching pants, black boots and a cap. All British

Commonwealth Air Training Plan trainees wore what was called a wedge cap. All aircrew trainees wore a flash of white material on their caps, which indicated that the wearer was undergoing

training. With so many airmen on every base, it was essential to separate those undergoing aircrew training from those who were not.

Uniforms were required to take the harsh Canadian climate into account and therefore, depending on the season and the occasion, the airman's dress was different. For example, an airman

on duty would wear something different from while messing, just as an airman on duty in the summer would wear different clothing from that worn during the winter. Summer uniforms took on the same style but were made from a lighter weight and lighter colored fabric.

It was not until Canadian airmen served overseas in World War II that a shoulder badge was worn officially. The badge read "Canada" and was worn to show one's nationality. Each component of the uniform was to comply with regulation and this badge was no exception. The top of it was to be worn 3/4 of an inch below the shoulder seam. Airmen and air-women were required to wear this on both shoulders of all jackets except for overcoats, officers' mess jackets and bandsmen's dress jackets. Upon enlisting in the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan (BCATP), each airman and air-woman received the classification of Leading Aircraft-man (LAC) and Leading Aircraft-woman (LAW). This was displayed on their uniform by the propeller badge worn on both shoulders. Once trained in a specialized capacity, each trainee would receive a new classification and a new badge to display this. Airmen were granted their Wings in graduation ceremonies and often rushed back to the barracks to stitch the badge on to the uniform. Wing badges were worn on jackets on the left side over the chest.

Serial Numbers

of Halifaxes known to be in the 432 Squadron:

LK754 (aka MZ-504) -QO-Z Fairey-built Halifax B III, entered service Jan-Jun

1944 (104 built LK747-LK887) -432 Sqdn QO:? PILOT Reid, Earle K F/O RCAF+. CREW

Sgt J A May+, F/O J T Smith RCAF pow, WO2 V C MacDonald RCAF pow, F/S G G

Maguire RCAF pow, Sgt R L Clarkson RCAF+, Sgt J J Barr RCAF pow. DETAILS NOTE

believe that the aircraft LK754 should really be LW687. TO 2158 East Moor. Outbound,

shot down by night fighter and crashed on a railway line SSE of Freidburg, 7 km N of

Frankfurt.Crew on 10th operation; 3 killed now in Durnbach War Cemetery. NOTE:

Evidence is showing that LK754 survived the war and was scrapped in 1947. The

Halifax that actually was lost appears to have been LW687.

LK755 -QO-K Halifax B Mk 3, no ops recorded with 432 at East Moor, transferred to

426 Sqd and later returned to East Moor with 415 Sqd., 21 ops recored with 415 Sqd.

"6U-KandD" and later transferred to HCU.

LK761 -QO-B Halifax B Mk 3, no ops recorded at East Moor, crashed during a night

exercise near Stillington at 9:43 hrs. 16/12/44.

LK764 -QO-F Fairey-built Halifax B Mk 3, entered service Jan-Jun 1944 (104 built

LK747-LK887) -Flew with 432 until July 1st, 1944...then went to 434 squadron until

Sept. 1944, then was transferred to 659 HCU...soc 28/Feb/1947. 25 ops before

transfer to 434 Sqd.

LK765 -QO-H Halifax B Mk 3, 4 ops recorded as "H" and a further 38 as "B" before

transfer to 415 Sqd., 20 ops with 415 Sqd. "6U-B" and later transferred to HCU.

LK766 -QO-V Halifax B Mk 3, 2 ops, swung on a 3 engined landing ex Metz, 00.22

hrs, 29/6/44, repaired and transferred to 415 Sqd. 34 ops recored with 415 Sqd.,

"6U-VandQ" and transferred to 187 Sqd.

LK799 -QO-W Halifax B Mk 3, Failed to return from Frankfurt on it's 5th recorded

operation, 23/3/44.

LK803 -QO-Z Halifax B Mk 3, 6 ops recorded at East Moor before transferred to 420

Sqd.

LK807 -QO-J Halifax B Mk 3, Failed to return from Montzen on it's 13th recorded

operation, 28/4/44

LK811 -QO-N Halifax B Mk 3, Failed to return from Bourg Leopold, 14th operation,

crashed Beverloo, 28/5/44

LK868 -QO Halifax B Mk 3, No ops recorded at East Moor, transferred to 431

Sqd.

LL432 -Rootes-built Halifax B/A/Met Mk 5 srs 1a, entered service Jan-Jun 1944 (411

built LL167-LL542) no history on this aircraft

LL547 -QO-X Rootes-built Halifax B Mk 3, entered service May-Jun 1944 (60 built

LL543-LL615) -Flew from Jun 6, 1944 until Jun 25, 1944....Then off to 429, 425 and

644....soc 22/Feb/1046 -10 ops recorded before transfer to 429 Sqd.

LW412 -QO-P Halifax B/A Mk 3, 2 ops recorded at East Moor before transfer to a

HCU

LW437 -QO-Halifax B/A Mk 3, No ops recorded at East Moor before transfer

to 434 Sqd.

LW552 -QO-S Halifax B/A Mk 3, 15 ops recorded before transfer to 415 Sqd., 35

ops recorde with 415 Sqd., "6U-S" crashed on take off at East Moor, 8/8/44

LW576 -QO-L Halifax B/A Mk 3, No ops recorded at East Moor before transfer to

to 431 Sqd.

LW582 -QO-M Halifax B/A Mk 3, Failed to return from Aucheres on it's 25th

operation, 8/6/44

LW583 -QO-L Halifax B/A Mk 3, Failed to return from Haine St. Pierre on it's 11th

operation, 9/5/44

LW584 -QO-Y Halifax B/A Mk 3, Failed to return from Frankfurt on it's 14th

recorded operation, 23/3/44

LW592 -QO-A Halifax B/A Mk 3, Failed to return from Montzen on it's 17th

recorded operation 28/4/44 -BURROWS, F/O John Woollatt (J22599), Killed in Action,

buried in Belgium -DRIVER, P/O Paul Edward (J85612), Killed in Action, buried in

Belgium

LW593 -QO-O Halifax B/A Mk 3, Failed to return from Berlin on it's 6th recorded

operation, 25/3/44

LW594 -QO-G Halifax B/A Mk 3, Failed to return fromHaine St. Pierre on it's 19th

recorded operation, 9/5/44

LW595 -QO-Q EE-built Halifax B/A Mk 3, entered service May-Jun 1944 (185 built

LW459-LW724) -Flew from Mar 1, 1944 until Jul 7, 1944, then sent to 415

Squadron...missing over Hamburg Jul 29, 1944 -34 ops recorded before transfer to

415 Sqd., 2 ops with 415 Sqd., "6U-Q" failed to return from Hamburg, 29/7/44

LW596 - QO-D Halifax B/A Mk 3, 31 ops recorded before transfer to 434 Sqd.

LW597 -QO-C Halifax B/A Mk 3, Failed to return from Augsburg on it's 1st

recorded operation. 26/2/44

LW598 -QO-K Halifax B/A Mk 3, 0 ops recorded before crashing at Newton on

Ouse due to the starboard inner engine having failed aircraft burnd out. 9/6/44

LW614 -QO-S Halifax B/A Mk 3, 9 ops recorded before crashing at Hackness due

to engine failure during air to air firing exercisw off Scarborough, 12/4/44

LW615 -QO-U Halifax B/A Mk 3, 17 ops before crashing into buildings after overshoot at East Moor during training and familiarization flight. 7/5/44

LW616 -QO-R Halifax B/A Mk

3, Failed to return from Cambrai on

it's 22nd recorded operation,

13/6/44

LW617 -QO-J Halifax B/A Mk

3, 7 ops recorded before transfer

to 158 Sqd.. Had suffered an u/c

collapse after skidding on ice

during a landing at East Moor at 18.27 hrs, 4/3/44

LW643 -QO-E Halifax B/A Mk 3, Failed to return from Noisy le Sec on it's 6th

recorded operation, 19/4/44

LW682 -QO-C EE-built Halifax B/A Mk 3, entered service May-Jun 1944 (185 built

LW459-LW724) -This aircraft flew 2 ops and was damaged in training.. it was fixed off station and then given to 426 squadron.. There it was coded OW-M. It went missing on May 13,1944 to Louvain Belgium..The crew was killed. Some of the parts are being used to rebuild the Halifax in Trenton Ontario. visit www3.sympatico.ca/scott.knox/

to see some pics of the recovery of 3 crew members and aircraft parts. -6 ops

recorded as "C" and a further 5 as "W" before transfer to 426 Sqd. -Recovery of

remains of the missing crew of LW682 -More on the recovery of LW682

LW686 -QO-H Halifax B/A Mk 3, 28 ops recorded before transfer to 415 Sqd.,

"6U-H" overshot East Moor u/c collapsed, 8/8/44

LW687 (aka LW682) -QO-C EE-built Halifax B/A III, entered service May-Jum

1944 (185 built LW459-LW724) -432 Sqdn QO:C PILOT Narum, C R F/O RCAF+. CREW Sgt R Thomson+, F/S R P Goeson RCAF pow, Sgt L E Pigeon RCAF pow, F/S A H Marini RCAF pow, Sgt W R Rathwell RCAF+, Sgt S Saprunoff RCAF+. DETAILS NOTE believe that the aircraft LW682 should really be MZ504. TO 2208 East Moor. Outbound, shot down by night fighter (Oblt Martin Becker) and crashed at Grossmaidscheid, 17 km NNE of Coblenz. Crew on 5th operation; 4 killed 3 PoW. Oddly, the three RCAF members

of the crew who died have been taken into Belgium for burial at Heverlee War

Cemetery, whilst Sgt Thomson lies in Rheinburg War Cemetery. -Failed to return from Nuremburg on it's 7th recorded operation, shot down by night fighter and crashed Friedburg 31/3/44 (Ref. "The East Moor Experience")

MZ504 -QO-Z EE-built Halifax B Mk 3, entered service Mar-Aug 1944 (40 built

MZ500-MZ539) -Went down over Nuremburg on Mar 31, 1944, service with 432 unknown -Failed to return from Nuremburg on what is believed to be it's 1st op from East Moor, shot down by a night fighter and crashed at Grossmaishe, Koblenz.

*unfortunately, conclusive.

the available information relating to MZ504 and MZ588 is not MZ506 -QO-X

23/5/44

MZ536 - QOMZ585 -QO-O

Halifax B Mk 3, Failed to return from Le Mans on it's 12th operation,

No ops recorded at East Moor before transfer to 431 Sqd.

Halifax B Mk 3, 9 ops recorded as "O" and a further 3 as "Z" before

transfer to 415 Sqd., 25 ops with 415 Sqd. "6U-Z", MZ586 - QO-Y Halifax B Mk 3, 23 ops recorded before transfer to 415 Sqd., 30 ops with 415 Sqd., 30 ops with 415 Sqd. "6U-YandA" transferred to 187 Sqd.

*MZ588 -QO-E Halifax B Mk 3, Failed to return from Montzen on what is believed to be it's 1st operation, 28/4/44 *unfortunately, the available information relating to MZ504 and MZ588 is not conclusive.

MZ590 -QO-C Halifax B Mk 3, 13 ops recorded before transfer to 415 Sqd., 11

ops with 415 Sqd., "6U-C", transferred to HCU.

MZ591 -QO-K Halifax B Mk 3, Failed to return from Metz on it's 14 recorded

operation, 29/6/44

MZ601 -QO-A Halifax B Mk 3, Failed to return from Cambrai on it's 11th recorded

operation, 13/6/44

MZ603 - QO-E Halifax B Mk 3, 27 ops recorded before tranfer to 415 Sqd.

MZ632 -QO-W Halifax B Mk 3, 25 ops recorded before transfer to 415 Sqd., 46 ops with 415 Sqd., "6U-W" transferred to HCU.

MZ633 -QO-O Halifax B Mk 3, 21 ops recorded before transfer to 415 Sqd., 4 ops with 415 Sqd., "6U-B", collided with NA609 near Selby at 18.12 hrs, 21/8/44

MZ653 - OQ-Halifax B Mk 3, No ops recorded at East Moor MZ654 -QO-L Halifax B Mk 3, 13 ops recorded before transfer to 415 Sqd., 30 ops with 415 Sqd., "6U-L" transferred to HCU.

MZ656 - QO-Halifax B Mk 3, No ops recorded before transfer to 431 Sqd.

MZ660 -QO-J Halifax B Mk 3, 23 ops recorded before transfer to 415 Sqd., 29

ops with 415 Sqd., "6U-J" transferred to HCU MZ672 - QO-G Halifax B Mk 3, 5 ops recorded before transfer to 429 Sqd.

MZ674 - QO-Halifax B Mk 3, No ops recorded before transfer to 425 Sqd.

MZ686 -QO-U Halifax B Mk 3, 17 ops recorded before transfer to 415 Sqd., "6U-U" crashed on take off East Moor, 22.18hrs, 28/7/44

NA500 -QO-G Fairey-built Halifax B MK 3, entered service Apr-Jul 1944 (85 built

NA492-NA587) -Missing over Bologne, 12 May, 1944 -Failed to return from Bologne

sur Mer on it's 1st recorded operation, 12/5/44

NA516 -QO-F Halifax B Mk 3, 2 ops as "F", transferred to 434 Sqd., retrurned to 432 Sqd. where a further 3 ops are recorded as "A" before failed to return from Sterkrade-Holten on it's 5th East Moor operation, 17/6/44

NA517 -QO-R Halifax B Mk 3, 9 ops recorded before transfer to 415 Sqd., 7 ops with 415 Sqd., "6U-R" overshot runway at East Moor, wilst fully laden after ops to Gaen, 01.06hrs, 6/8/44, transferred to 190 Sqd.

NA527 - QO-N Halifax B Mk 3, 12 ops recorded before transfer to a HCU

NA550 -QO-Halifax B Mk 3, No ops recorded at East Moor before transfer to

434 Sqd.

NA552 -QO-Halifax B Mk 3, No ops recorded at East Moor before transfer to

434 Sqd.

NP687 -QO-A Halifax B Mk 7, 10 ops recorded, failed to return from Stuttgart,

26/7/44

NP688 -QO-X Halifax B Mk 7, entered service Jun-Jul 1944 (43 built NP681NP723) -Missing Stuttgart, 26 July, 1944 -7 ops recorded, failed to return from Stuttgart, 26/7/44

NP689 -QO-M Halifax B Mk 7, 85 ops recorded, failed to return from Hagen,

15/3/45 -Flight Sergant T.D. Scott , who was member of the 6. RCAF Squadron. In

March 1945 he was listed in the crew of the Halifax NP 689 *M*. F/S Scott was

murdered by the local Hagen Gestapo office after his balling out in the operation

against Hagen on 15/16 March 1945. This raid would be his last operation and he

wanted to return home. His body was found in May 1945 by the US-Army in a bomb crater. The Gestapo team were found guilty in September 1946 by an Canadian military court, the Hagen Gestapo chief was executed in Hamel prison in January 1947.

NP690 -QO-G Halifax B Mk 7, 20 ops recorded, crashed on take off, East Moor and burned, 18/08/44

NP691 -QO-V Halifax B Mk 7, 62 ops recorded, Damaged beyond repair by night fighter, ex Grevenbrioich, 15/01/45

NP692 -QO-D and K Halifax B Mk 7, crash landed Woodbridge, burnt, ex Brttrop,

27/9/44

NP693 -QO-Q and K Halifax B Mk 7, entered service Jun-Jul 1944 (43 built NP681NP723) -Flew from July 9, 1944 to end of war -71 ops recorded

NP694 - QO-R Halifax B Mk 7, 85 ops recorded

NP695 - QO-K Halifax B Mk 7, 39 ops, failed to return from Osnabruck, 6/12/44

NP697 - QO-F Halifax B Mk 7, 80 ops recorded

NP698 -QO-U and X Halifax B Mk 7, entered service Jun-Jul 1944 (43 built NP681NP723) -Flew from July 4, 1944 until end of war....soc 30 Dec 1949 -61 ops recorded

at 15.12 hrs on April 25, 1945, piloted by "Bud" Raymond (my Dad's flight crew) this plane was the last plane to leave East Moor in anger. This was the last operation of WW2 from East Moor.

NP699 -QO-O Halifax B Mk 7, 42 ops recorded, failed to return from Duisburg,

collided with aircraft over Belgium, 18/12/44

NP701 -QO-Sand G Halifax B Mk 7, 36 ops recorded, failed to return Duisburg,

18/12/44

NP702 - QO-B Halifax B Mk 7, 8 ops, failed to return from Hamburg, 29/7/44

NP703 -QO-H Halifax B Mk 7, entered service Jun-Jul 1944 (43 built NP681NP723) -Flew from Jul 11, 1944 until end of war....soc 11 May 1945 -58 ops recorded

NP704 -QO-L Halifax B Mk 7, 56 ops recorded, failed to return from Wanne Eickel,

3/2/45

NP705 - QO-Y Halifax B Mk 7, 82 ops recorded

NP706 - QO-J Halifax B Mk 7, 3 ops recorded, failed to return Caen, 18/7/44

NP707 -QO-W Halifax B Mk 7, 67 ops recorded, overshot Ford, 05.06, 2/7/44,

repaired

NP708 - QO-E Halifax B Mk 7, 73 ops recorded

NP710 -QO-Halifax B Mk 7, No opps recorded at East Moor before transfer to

408 Sqd.

NP712 -QO-Halifax B Mk 7, No opps recorded at East Moor before transfer to

408 Sqd.

NP716 -QO-Halifax B Mk 7, No opps recorded at East Moor before transfer to

408 Sqd.

NP718 -QO-Halifax B Mk 7, No opps recorded at East Moor before transfer to

408 Sqd.

NP719 -QO-N Halifax B Mk 7, 21 ops recorded, failed to return from Kiel, collided

w/aircraft over target, 16/9/44

NP720 - QO-A Halifax B Mk 7, 9 ops recorded, transferred to 426 Sqd.

NP721 -QO-X Halifax B Mk 7, 22 ops recorded, overshot East Moor, 16.31 hrs

6/8/44, repaired, crashed and burnt on take off at East Moor, 18.06, 5/12/44

NP722 -QO-S Halifax B Mk 7, 30 ops recorded, crash landed at Manston at 21.03

hrs, ex Essen previously, Car. B at East Moor 04.31 hrs ex Kiel, 23/10/44

NP723 -QO-D Halifax B Mk 7, 28 ops recorded, failed to return from

Wilhelmshaven, 15/10/44

NP736 -QO-B Halifax B Mks 3,6,7 , entered service Aug-Dec 1944 (157 built

NP736-NP927) -Flew from Aug 5, 1944 until end of war....soc 30 Dec 1949 -59 ops recorded, damged by NP755 which was landing at Croft, ex Munster 18.30 hrs,

18/11/44, repaired

NP738 -QO-J Halifax B Mk 7, 21 ops recorded, crashed into trees, Woodbridge, ex Wanne Eickel

NP755 -QO-A Halifax B Mk 7, 69 ops recorded, landing accident with NP736 at

Croft, repaired

NP759 -QO-CandO Halifax B Mk 7, 35 ops recorded, failed to return from Hannover,

5/10/45

NP774 - QO-Z Halifax B Mk 7, 38 ops recorded

NP778 -QO-Halifax B Mk 7, Halifax B Mk 7, No opps recorded at East Moor

before transfer to 426 Sqd.

NP779 -QO-Halifax B Mk 7, Halifax B Mk 7, No opps recorded at East Moor

before transfer to 426 Sqd.

NP797 - QO-NandC Halifax B Mk 7, 21 ops recorded before transfer to 426 Sqd.

NP801 -QO-N Halifax B Mk 7, 7 ops recorded, failed to return from Bochum,

9/10/44

NP802 -QO-SandO Halifax B Mk 7, 21 ops recorded, collided w/aircraft while

landing at Linton on Ouse 17.15 hrs, 24/12/44 ex Dusseldorf, repaired.

NP803 -QO-E Halifax B Mk 7, 35 ops recorded, failed to returm from Worms,

22/2/45

NP804 - QO-Q Halifax B Mk 7, 22 ops recorded, transferred to 408 Sqd.

NP805 -QO-J Halifax B Mk 7, 40 ops recorded, crashed on takeoff, East Moor,

12.10 hrs, 16/04/45

NP807 -QO-P Halifax B Mk 7, 27 ops recorded, swung om fakeoff, became bogged down, 16/1/45, transferred to 408 Sqd.

NP808 - QO-N Halifax B Mk 7, 1 op recorded, transferred to 426 Sqd.

NP812 - QO-T Halifax B Mk 7, 21 ops recorded

NP813 -QO-Halifax B Mk 7, no ops recorded at East Moor, transferred to 426

Sqd.

NP815 - QO-H Halifax B Mk 7, 8 ops, failed to return from Gelsenkirchen, 6/11/44

NP817 -QO-D Halifax B Mk 7, 20 ops recorded, failed to return from Hannover,

5/1/45

NP961 - QO-D Halifax B Mk 7, 7 ops recorded, transferred to 415 Sqd.

NP968 -QO-Halifax B Mk 7, no ops recorded at East Moor, before transfer to

466 Sqd.

NP971 -QO-Halifax B Mk 7, no ops recorded at East Moor, before transfer to

466 Sqd.

PN208 - QO-G Halifax B Mk 7, 27 ops recorded

PN224 -QO-O Fairey-built Halifax B/A Mk 7, entered service Feb-Mar 1945 (46

built PN208-PN267) -Flew from Feb 27, 1945 until end of war....soc 1 June 1945 -18 ops recorded

PN229 - QO-C Halifax B Mk 7, 20 ops recorded

PN233 - QO-D Halifax B Mk 7, 18 ops recorded

PN235 -QO-S Halifax B Mk 7, 13 ops recorded, crashed on takeoff, East Moor,

16/4/45

PN236 - QO-Halifax B Mk 7, No ops recorded before transfer to 415 Sqd.

PN237 -QO-Halifax B Mk 7, No ops recorded before it swung on to East Moor at 14.59 hrs, 16/4/45, repaired and transferred to 415 Sqd.

PN241 -QO-I Fairey-built Halifax B/A Mk 7, entered service Feb-Mar 1945 (46

built PN208-PN267) -Flew from Mar 15, 1945 until end of war....went to 1665

HCU....soc 1 June 1945 -10 Ops recorded before transfer to HCU

RG448 - QO-V Halifax B Mk 7, 26 ops recorded

RG449 - QO-S Halifax B Mk 7, 5 ops recorded, failed to return Chemnitz, 15/2/45

RG450 - QO-Q Halifax B Mk 7, 8 ops recorded

RG451 -QO-D EE-built Halifax B Mk 7, entered service Jan-Mar 1945 (20 built

RG447-RG479) -Missing over Worms Germany, 22 Feb 1945

RG454 - QO-P Halifax B Mk 7, 22 ops recorded

RG455 - QO-X Halifax B Mk 7, 5 ops recorded, failed to return Monheim, 21/2/45

RG475 -QO-L Halifax B Mk 7, 8 ops recorded, shot down by "friendly" ex

Chennitz, 6/3/45

RG476 -QO-T Halifax B Mk 7, 1 Op recorded, failed to return from Worms,

22/2/45

RG478 - QO-U Halifax B Mk 7, 18 ops recorded

RG479 - QO-N Halifax B Mk 7, 16 ops recorded

NR145 - QO-C Halifax B Mk 7, 3 ops before transfer to 415 Sqd.

Mission to Berlin

March 8, 1944

By Art Livingston

Editor's note: The following is from a letter written by Art Livingston and sent

to the brother of Alva Hood, who was killed during this mission along with his entire

crew. Hood and his crew shared a hut with the author. The letter begins with a very brief introduction; we skip to the day of the mission. Gibb would have had similar

experiences.

Now to the day of the crash, March 8, 1944. We were awakened about 3AM and each of us would have gone to the latrine to shave as whiskers didn't allow the oxygen mask to fit tightly. Then back to the hut and dress for the mission. Most of us would have put on our long-johns, wool shirt, and pants, gabardine flying suit and flight jacket.

Two or three pairs of socks. Then we would have walked to the mess hall at about 4AM for breakfast. We always got a good breakfast of real eggs cooked any way you liked them, cereal, and meat of your choice. Always an orange you would take for after the mission or to take into town to give to a British kid, some whom never even saw an orange before. Leaving the mess hall you would walk with your crew or others to the briefing room.

There were guards there to see that no outsiders could get in and find out the

mission and tip off the enemy. When you came in it was like a large theater with a stage and we sat on wooden benches. On the stage was a large easel about 12 X 8 feet. It was covered over so you could not see what was under it. After the room was full someone called "tenshun" and we all stood up as the Commanding Officer walked up to the stage.

Then the cover was removed and you saw a map of Europe. There would be a red

ribbon extending from England to the intended target. If the tape was long, a large

groan went up from each man in the room. If short, a sigh of relief. This day the tape was long and went all the way to Berlin.

This was only the second time the 8th AF bombed Berlin. We were briefed as to

the route that would take us through the lightest flak concentrations, where we could

expect to be jumped by the GAF and what our escort would be. Then the weather officer would advise the cloud conditions and whether we could bomb visually or drop on a flare furnished by a pathfinder ship that had radar that could penetrate the clouds. Then the navigators would be briefed as to the headings we should take and the times it should take to get to the target. Then the bombardiers would be shown photos of the target that were flashed on the screen and how to get his Norden bombsight to get the best results. Now we went to the dressing area where we dressed for the mission. I put on the light blue electric suit that was cut like a large pair of long-johns. It was wool and had hundreds of wires going thru it like an electric blanket. At the wrists and ankles, wires protruded so you could attach the electric gloves and boots. Then I put the A2 jacket on and over the sheepskin leather jacket and pants. Then the fleece lined flying boots and we were ready to go. On the way out of the dressing room, there was a table where you turned in your wallet and anything that would aid the enemy in case you were shot down. Also at this time you were given your escape kit. It was a plastic bag about 10 X 10 inches and quite flat, so you could tuck it under your clothes. In it were silk maps of any country you were flying over as well as currency for those countries so you could bribe your way out. Also a photo of yourself in shabby clothes and needing a shave that would be used to make you a false passport. This later turned out to be a joke, as the Germans noticed each guy was dressed out in the same old suit and they could even tell

you what group you were from. There was a small compass the size of a pencil

eraser, water purifying pills, and pep pills to get you off to a flying start after you

hit the ground and buried your chute. There were a couple of pieces of British chocolate so horrible we didn't even steal it. And there were a few first aid items. The last thing we picked up was our parachute bag that held it and it's harness

and we stored our shoes in it in case we had to bail out with nothing but our flight

boots which were no good for walking. We went out to the building where the trucks were parked. When we got there it was probably about 6AM and still dark, but the ground crew was working on the ship all night loading bombs, gasoline, and running up the engines to make sure they were perfect. They had various lights on around the ship so we could see. Each crew position went about checking it's own area. The pilots and engineer checked the engines, controls and instruments. The radio man checked his set and changed the crystal to the one that would be used that day. The navigator laid out his charts at his position next to the bombardier who was hooking up his secret Norden Bombsight that was removed from the ship after each mission and stored in a vault for security reasons.

My job as armorer/gunner was to inspect the bombload to see if it was done

correctly. It always was, but we had to be certain. Each bomb had 2 fuses to be certain it exploded on contact, one in the nose and one in the tail. For safety reasons, the bombs had to be safe while on the ground and only armed when we got in the air. This was done by installing a small aluminum prop that would spin off the fuse as it went toward the ground. To hold the prop in place so it wouldn't spin off accidentally, there was a cotter pin that held it in place. After we became airborne, it was my job to enter the bombay and remove the pins. To make sure this was done, I had to report to either the pilot or bombardier for them to count the pins I removed, 2 for each bomb. The worst thing for a bomber was to go all the way to a target only to have the bombs fail to explode. I also had to check each turret position to see if it had been restocked with ammo and made sure the turrets were in working order.

By now it's near seven, which was usually the time for take off. The pilot got

us all into our positions for take off. The planes all lined up at the end of the runway

waiting for the signal from the control tower. The first ship got the flare and started down the runway followed by the rest of us at thirty second intervals. There was s strict procedure what a ship had to do when airborne so they wouldn't crash into each other. Each group had a war weary B-24 painted up in outlandish colors that was the formation ship. Ours was yellow and black and was called "Fearless Freddie". It took about an hour to get the group formed and then we formed on the lead group that led us to the bomber stream that was made up of about a dozen groups of 48 ships each. The lead group led us all to the target. They dropped their bombs first and we all dropped on their bombs as we got over the target.

This day it was clear and you could see the ground all the way to the target and

back. Over Berlin the town looked unhurt as the bomb damage wasn't apparent from about 28,000 feet. I saw the stadium where the 1936 Olympics were held and Hitler

showed off his supermen. We neared our target area and got on the bomb run. This is when the bombardier is steering the ship by the bomb site. He opens the bay doors and salvos the bombs when on the target. The ship leaps up when that weight is gone. I watch the bombs go all the way down and hit the target. This day we hit it well and then we turn for home.

As we were flying to and from the target we were set upon by various fighters at

different times. They would come at you one after another from all different

angles and usually each gun position would get a chance to hit one. While this was going on our friendly fighters tried to keep them away. The dog fights were very interesting and you cheered when one of theirs went down and sorrowed when it was one of ours. Ours usually had the upper hand as we had more and and a little better planes. I saw 5 B-24's go down. This was not all at once but throughout the mission. As you saw a ship go down you would call the navigator so he could log the exact area and whether there were any chutes exiting the doomed ship. This way headquarters could check out the crash and notify the families whether it was KIA or MIA. I know 2 of the downed ships were from our group but didn't know which ones till we got back down. We made it back to base and went into interrogation where the interviewers asked about all phases of the mission. Usually a bottle of spirits sneaked it's way to the table to loosen up the tongue. At this time each person told what he had seen and the number of planes shot down, the type and chutes if any. Also the damage to the target if you could see where the bombs landed. This is where I learned one of the missing planes was your brother's. All of us were stunned by this news. We left the interrogation and walked back to the hut.

All of us were a little shaken and it was eerie walking into that hut and

looking down to the other end of it and knowing it would be empty. All of that crew's belongings were just where they left them that morning. All the uniforms hanging in a row, pictures of their families on display, shoes lined up under their bunks, and all the items they enjoyed.

My crew just fell on their bunks and each had a thought about why them and not

us. We were very quiet. By now it was about 4 in the afternoon. The door to our hut

opened and 3 men we didn't know entered and asked where the Helfers crew slept.

the location and and they started to lay out the men's belongings in 2 piles.

One for government issue which would be recycled and the other pile of the men's

personal belongings that would be sent home to the families. Each item was recorder and packed into various bags. When all the items were packed they took off the blankets and mattress covers from each bunk, folded up the mattresses, and left with all the bags.

That was the end of that story.

In a day or so a replacement crew appeared and took over the bunks and hung up

their clothes and pictures and it started all over again. It was said you didn't want

to make too many friends in the army. Then you wouldn't miss them so much if they were killed.